In the comments of my post Choosing a date for a DBA-RRR game in the Italian Wars John Rohde pointed out I had got the results of the Battle of Fornovo (6 July 1495) wrong. This was the second major field battle of the Italian Wars. In a short but brutal fight the French gendarmes proved their superiority over their Italian counterparts.

Setting: River Taro, north of Fornovo, Italy; 6 July 1495

Situation

In 1494 King Charles VIII of France decided to exert his Angevin claim to the throne of Naples (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). By May French officials were in Piedmont and Genoa preparing the way for the army to follow. The troops began arriving in June. In late August Charles VIII crossed the alps himself and joined his main force at Piacenza on 18 October.

Charles VIII then paraded down Italy to take Naples (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). There was little resistance. The Duchy of Milan (Ludovico Sforza) was allied to France and, with some reservations, assisted the invaders. The minor French states of Savoy, Lucca, and Siena let the French pass their territory unhindered. The Roman Barons were either in French employee or disinclined to resist. Florence (Piero de Medici) was treated as hostile until cowed into submission. The first Florentine fortress, Fivizzano was taken by stealth, sacked, and all the defenders and many of the inhabitants killed. Other Florentine fortresses surrendered or suffered the same fate. Florence opened its gates to Charles VIII on 17 November. Pope Alexander made no attempt to stop the the French and shut himself up in Castel Sant Angelo as the French occupied Rome. The Pope then conceded free passage and provisions for the French army, and gave temporary tenure of key Papal fortresses. Early in the campaign the Neapolitans tried to invade Milan from the south and through Genoa but with no success. On 9 Feb 1495 the French took the Neapolitan fortress of Monte San Giovanni by storm and killed several inhabitants; only a few survived. Other Neapolitan towns opened their gates to the French. Charles VIII entered Naples on 22 February but French troops were in the city exchanging fire with the Neapolitan held fortresses. It took three weeks for the fortresses to be subdued.

Within weeks of Charles VIII taking Naples, the French began talking about the king returning to France (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). Charles wanted to be back in France before the heat of the summer. They were, however, aware that this might involve a fight.

Although neutral Ferdinand of Aragon began moving troops and ships to Sicily over the winter of 1494-5 (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). He also began discussing an anti-French alliance with Venice, and the Emperor-elect Maximilian. The Venetians also worked on detaching Ludovico Sforza (Duke of Milan) from France. On 31 March 1495 these parties signed “a defensive league against unprovoked aggression by any power holding a state in Italy – which would now include Charles – against any of the signatory Italian States” (p. 27). This was known as the League of Venice or the Holy League.

Charles VIII left Naples on 20 May 1495 although some French contingents had marched north earlier (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). Naples was held with 800 French lances, 500 Italian lances and 2,700 infantry. The king had 1,000 lances and 6,000 infantry as an escort.

By the end of June 1495 the Holy League had a substantial army mobilised near Parma under Marquis Giovanni Francesco Gonzaga of Mantua (Oman, 1937; Mallet & Shaw, 2014). They were waiting for the French to come through the mountains.

Meanwhile the captain of the King’s Scottish Archers, Bernard Stewart, Lord of Aubigny, defeated Gonsalvo de Cordova, known to history as the Great Captain (El Gran Capitán), at the Battle of Seminara (28 June 1495).

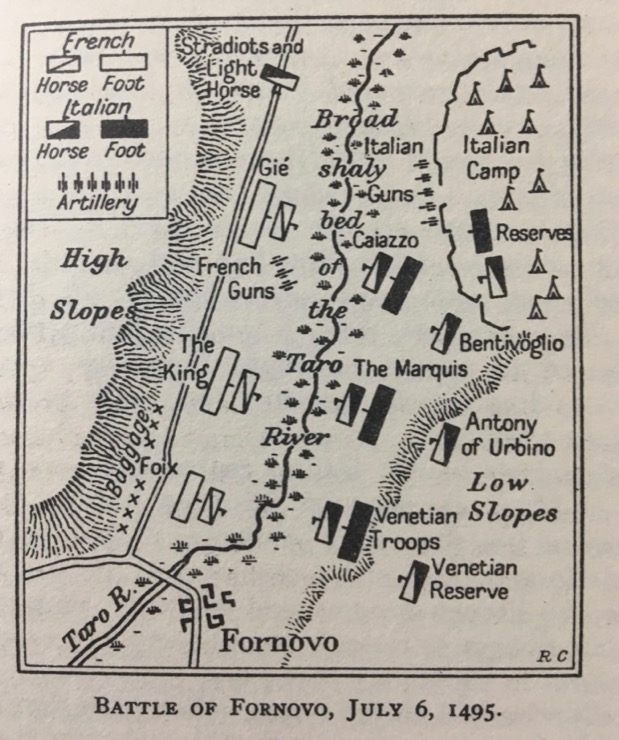

Map

Fornovo was fought across the River Taro. The Holy League were camped on the right bank of the River Taro. The French approached from the south along the track on the opposite side of the river. Heavy rain overnight had swollen the river and the men found the river bed slippery and the banks muddy. The Italians expected to cross in four locations but found only three practicable.

Orders of Battle

French Order of Battle

In the parade down Italy the Venetian Marino Sanuto described French army as “these strange types, French, Swiss, Gascons, Picards, Scots and Germans” (Mallet & Shaw, 2014, p. 24).

Mallet and Shaw (2014) give the French had 10-11,000 men at the battle. Oman, quotes Comines who quotes Niccolo Orsini, Conte de Pitigliano, who was a hostage with the French, and gives the French 9,000 men. The vanguard was the biggest battle with all the Swiss and artillery. Oman (1937) gives the French order of battle as:

- Commander: King Charles VIII

- Vanguard (Pierre de Gié and Giangiacomo Trivulzio)

- 350 Men-at-arms

- 200 Mounted Crossbowmen of the royal guard, fighting on foot

- 300 Crossbowmen

- 3,000 Swiss Pikemen (Engelbert of Cleves)

- All of the Artillery

- Main battle (Charles VIII)

- 300 Men-at-arms

- 2,500 Crossbowmen

- Rear guard (Count of Foix)

- 300 Men-at-arms

- 2,500 Crossbowmen

- Baggage Train

Holy League Order of Battle

Mallet and Shaw (2014) give tThe Holy League had about 20,000 men, but Oman (1937) gives them 14,000. Either way they had about 50%-60% more troops than the French.

This is the Holy League orbat in Mallet and Shaw (2014):

Holy League Order of Battle – Mallet and Shaw (2014)

- Commander: Marquis Giovanni Francesco Gonzaga of Mantua

- River Crossing Force

- Right flank (to attack French left and rear)

- Venetian Stradiots

- Centre

- 5,000 Milanese (Gianfrancesco da Sanseverino)

- Left flank (to attack French right and rear)

- Venetian heavy cavalry (Francesco Gonzaga)

- Venetian heavy cavalry (Bernardino Fortebraccio)

- 10,000 men in total, split evenly between Milanese and Venetians

- Right flank (to attack French left and rear)

- Reserve on the far side of the river1

- Another 10,000 Venetians including:

- Venetian Militia

- Another 10,000 Venetians including:

Note:

(1) Roldolfo Gonzaga was to call forward the reserves as needed.

Oman (1937) gives the allies:

Holy League Order of Battle – Oman (1937)

- 2,400 Men-at-arms from Venice, Milan or minor princes

- 2,000 light cavalry

- 1,200 Mounted Crossbowmen

- 600 Stradiots

- More than 10,000 infantrymen, many no better than camp-followers

- Mostly crossbowmen

- Some German pikes

Oman (1937) goes on to give the deployment of the Holy League

Holy League Deployment – Oman (1937)

- First line

- Artillery to fire across the river

- Extreme Right

- 600 Stradiots (Pietro Duodo)

- 700 Mounted Crossbowmen (Alessio Beccacuto)

- Right Wing: Milanese (Count Giovanni Francesco of Caiazzo)

- 600 Milanese Men-at-Arms

- 3,000 Milanese Infantry including some Germans

- Main Battle (Marquis Giovanni Francesco Gonzaga of Mantua)

- 500 Veteran Italian Men-at-Arms, mainly from Mantua and minor allies

- 500 Mounted Crossbowmen

- 4,000 Infantry

- Left Wing

- 500 Venetian mercenary horse (Fortebraccio de Montone)

- Second line

- Right Wing Reserve

- Milanese Horse (Annibale Bentivoglio and Galeazzo Palavicino)

- Main Battle Reserve

- Troops from Marches and Papal States (Duke Urbino)

- Right Wing Reserve

- Left Wing Reserve

- Venetian Horse (Gambara of Brescia and Benzone of Crema)

- Camp Guard

- Detachment of horse

- A very large body of the least useful infantry

The Battle

Gonzaga camped the Holy League army on the right bank of the River Taro. The artillery was positioned to fire onto the track on the far bank, where the French were expected to appear.

The French army advanced down track on left bank of the Taro (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). All of the Swiss and the artillery were in the vanguard. Their job was to open the road against the expected Italian resistance. The Holy League artillery opened fire on the French vanguard as they came opposite, and Gie deployed his own artillery to answer, but kept the rest of the troops moving (Oman, 1937).

Gonzaga then sent his first line across the river to attack the French (Mallet & Shaw, 2014; Oman, 1937). The first line was divided into four groups, from right to left:

- Light horse

- Milanese heavy cavalry and infantry (Count Giovanni Francesco of Caiazzo)

- Italian heavy cavalry, light cavalry, and infantry (Francesco Gonzaga)

- Venetian heavy cavalry (Bernardino Fortebraccio)

The remainder of the Holy forces, half the total, remained on the far side of the river as a kind of reserve (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). Roldolfo Gonzaga has the authority to bring elements of the reserve forward during the battle, but Roldolfo accompanied his nephew into battle against the French and, in the end, none of these troops participated in the battle.

The river crossing was difficult because heavy rain overnight had swollen the river (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). The river bed was slippery and the banks muddy (Oman, 1937). The four bodies were meant to cross at different points, simultaneously. However, in practice, the crossings happened at different times and the battles of Gonzaga and Fortebraccio were forced to share a single crossing point.

The difficulty of the crossing gave the French time to form up (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). This was simply a right turn. From left to right, facing the river, the French battles were: vanguard, the main body, rearguard (Oman, 1937). The baggage train was a little up the hill side from the rearguard, away from the river and behind the battle line.

As planned the Italian light horse – mounted crossbowmen and Stradiots – blocked the French vanguard’s advance along the road (Oman, 1937). The Italian mounted crossbowmen then rode behind the French rear and attacked the guard of the baggage train (Wikipedia: Battle of Fornovo). The Stradiots, seeing the camp unguarded also rode to the French rear and sacked the baggage train and killed 100 camp followers. Mallet and Shaw (2014) claim some of the Holy League infantry also broke ranks to loot but I can’t see how this is possible. They’d have to fight their way through the French to do it.

The Milanese battle attacked the French vanguard (Mallet & Shaw, 2014). The Milanese men-at-arms seemed to have had a morale crisis and failed to charge home. Gié led the French Gendarmes in a counter-charge that drove the Italians back across the river (Oman, 1937). Gié spent the rest of the battle facing off the Milanese under Bentivoglio of the Holy Leagues’s right wing reserve.

According to Oman (1937) the Swiss, the majority within the French vanguard, charged the Milanese infantry and “made a great slaughter of them”. Oman cited Guicciardini and says the Germans, amongst the Milanese ranks, made for the French artillery, and were rolled over by the Swiss just as they reached the guns. [Mallet and Shaw (2014) caution that eye witnesses emphasise the clash of the heavy cavalry at Fornovo, but writers who were not present – and I suspect this was true of Guicciardini – give a prominent role to the French artillery and the rapid assaults of the French and Swiss.]

The decisive action was in the centre where Gonzaga clashed with Charles VIII and Italian left flank where the Venetian horse fought the Count of Foix (Oman, 1937). King Charles rode in the front rank of his heavy cavalry and the French gendarmes beat the Italian elmeti at the first clash. The Italians fled back across the river. The supporting Italian infantry also fled. [Mallet and Shaw (2014) say the Italian heavy cavalry found itself outnumbered in the centre but that doesn’t align with the orders of battle.]

There were heavy losses amongst the Italian men-at-arms (Oman, 1937). Gonzaga lost 60 of his personal entourage including his uncle Roldolfo (Oman, 1937). Roldolfo’s death left nobody with authority to call up the Holy League reserves (Mallet & Shaw, 2014) although by this stage of the battle they might not have been keen to cross the river anyway.

The Stradiots, and presumably the Italian light horse with them, saw the result of the battle and made off with what loot they could carry (Oman, 1937).

After one hour of fierce fighting the battle was finished (Mallet & Shaw, 2014; Oman, 1937). The Holy League had withdrawn back across the river. According to Guicciardini, and cited by Oman, the French had lost 200 men. The Holy League 350 men-at-arms and 3,000 infantry. The high losses amongst the Italians can partially be explained by the no quarter policy of the French.

Both sides claimed victory (Mallet & Shaw, 2014; Oman, 1937). The arguments can be summarised as:

- Italian victory: The French abandoned the field of battle (and Italy) and lost their baggage and 300,000 ducats worth of booty

- French victory: The Italians suffered more casualties and failed to stop the French leaving Italy

The official Italian version gave the victory to the Holy League but unofficially they acknowledge a French victory. Francesco Guicciardini’s verdict was:

the victory was universally adjudged to the French on Account of the great Disproportion of the slain, of their driving the Enemy on the other Side the River, and because their Passage was no longer obstructed, which was all they contended for, the Battle being fought on no other Account. (Guicciardini, 1753, p. 338-339)

References

Guicciardini, F. (1753). The History of Italy. Translated by Austin Parke Goddard. London: John Towers.

Mallet, M., & Shaw, C. (2014). The Italian Wars 1494-1559: War, State and Society in Early Modern Europe. London: Routledge.

Oman, C. (1987). A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. London: Greenhill Books. Originally published 1937.