Japanese infantry were already conducting “human bullet” assaults (nikuhaku kōgeki) against Soviet armour in 1939. In the absence of better anti-tank options they continued this practice throughout World War II, whether in China, the Pacific, or Burma. The death of the individual was accepted as the necessary price for the destruction of the tank, in accordance with the Japanese doctrine of “one soldier, one tank.” The goal was to combine honorable suicide with definite military results.

Japanese anti-tank doctrine

The Japanese had a three stage approach antitank tactics: (1) use antitank guns to destroy the tank; (2) use small arms to drive off the accompanying infantry to leave the tanks “blind”; (3) assault the tank with hand-carried explosives to either directly destroy the tank or at least immobilize it to allow it to be destroyed it later (modified from Huber, 1990).

Japanese doctrine was to withhold fire until the enemy tanks were quite close (Huber, 1990). This was true even though the 47 mm anti-tank gun could “perforate” Sherman armour out to 800 yards. When the enemy were close the Japanese soldiers attack the thanks with artillery and escorting infantry with small-arms and mortars. If this managed to separate the enemy tanks from the infantry, the Japanese would launch a “Human bullet” assaults (nikuhaku kōgeki) with tank hunter teams. Any Japanese infantry supporting the assault team, would try to isolate the tank from its infantry support and then directs fire at the tank’s observation ports.

Anti-tank artillery

Japanese doctrine was to use whatever anti-tank artillery there was before the tank hunter teams went in. This includes anti-tank rifles, anti-tank guns, and normal artillery.

Anti-tank rifles were rare. Only high priority ‘A’ Type Battalions were given anti-tank rifles (Japanese Leg Battalion – Revised Organisation for Crossfire). This was the rather heavy and inefficient Type 97 automatic cannon (Zaloga, 2018, cited in Wikipedia: Type 97 automatic cannon). Two Type 97s were issued to each rifle company in these privileged battalions. Each required a crew of 11 men and nine horses.

Anti-tank guns were far more common, although different units would have different numbers of guns. The anti-tank gun company of each Japanese infantry regiment had at 4-6 antitank guns (Huber, 1990). These were initially the 37mm anti-tank gun but from 1941 the far more effective 47mm weapon began to appear. In some divisions in the Pacific the anti-tank platoons were parcelled out to the battalions of the regiment. Independent anti-tank companies could provide an additional eight weapons and independent anti-tank battalions could offer 12-18 more guns.

Larger artillery pieces were also used in the anti-tank role (Huber, 1990). The battalion’s 70mm infantry gun and the 75mm regimental gun were both used to cover road blocks, antitank obstacles, and minefields. The Americans considered the Type 90 (1930) 75mm field gun to be a formidable antitank weapon because of its high muzzle velocity and 50 degree traverse (Military Intelligence Division, 1945).

Tank hunter teams

The Japanese organised individuals or small groups into “tank hunter” teams (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). These tank-hunter teams attacked tanks in battle and also after infiltrating into tank parks as small raiding parties. They are taught to direct their attacks against the most vulnerable points, including the tracks, the tank’s weapons, observation ports, periscopes, air vents, the turret, turret ring, and gun mantlet.

Tank hunters were quick to attack enemy tanks that had either outdistanced their infantry support, been slowed down by terrain, or were immobilised (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). Attacking a tank moving at 15 km per hour is difficult for a man on foot, so tank hunter teams were taught to attack at times and places where the tanks had to slow down. Preferred attacking locations were when the tank had to pass through difficult terrain such a anti-tank obstacles, defiles, narrow roads, fords, or rough trails through dense vegetation. They could attack at any time but preferred attacks at dawn, at dusk, or in rainy weather.

Tank Hunter teams were often two or three men (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). Each member of the tank-hunter team had a specific role. A two-man team would have the group leader, carrying a pole mine, and the Number 1, carrying a Molotov cocktail. The team would attack the tank simultaneously from both sides as it enters terrain favorable to the tank hunters.

A three man tank hunter team could attack in this way (Military Intelligence Division, 1945):

- Use smoke grenades or candles to obscure the attackers from the tank crew and its infantry support

- The Number 1 hurls a Molotov cocktail onto the tank to force the crew to abandon the tank, and if that was unsuccessful …

- The group leader would try to immobilise the tank with a antitank mine or demolition charge against the tracks (either by hand or using a pole charge)

- The Number 2 would try to destroy or damage the tank’s guns by placing an adhesive mine or some similar explosive under them

- Failing that, the assault team might attempt to climb onto the tank and force the hatches with small-arms fire and grenades

Each Japanese infantry platoon could have a tank hunting team (Military Intelligence Division, 1945).

Tank Hunter anti-tank Engineer team

The Japanese engineers were trained to attack in three coordinating sections (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). Each assault team attacked one tank and several assault teams could be deployed in depth in order to facilitate operations on successive tanks. Smoke, from candles, grenades, and/or artillery was used to neutralise the enemy tank. Generally an engineer assault team would have 6-9 men in three sections with an NCO leader. The three sections were:

Neutralisation section: 2-3 men lead the attack, attempt to create surprise and an opportunity for the following elements.

Track-destroying section: 2-3 men attack the tank on one side to try to destroy the tracks.

Demolition section: 2-3 men deliver the final blow with armour piercing explosives.

Platoon and Company anti-tank combat units

Infantry and engineers could form a platoon or company sized anti-tank combat unit (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). These units comprised:

- Several land-mine squads (firing squads)

- Several destruction squads

- A reserve squad

- Optional covering squad

Land-mine squad: The land-mine squads had 10 men under a NCO. They had two roles. Firstly they planted mines on likely approach routes. After that they provided covering fire with rifles and two or three light machineguns. They tried to separate the tanks from their escoring infantry.

Destruction squad: The destruction squad had several men under a NCO. Its role was to close assault the tank with mines and explosives and destroy it. They would attack under under covering fire by the Land-mine squad and/or smoke.

Reserve squad: The reserve squad could, when called upon, perform the duties of either tlhe land-mine or destruction squads.

Covering squad: The covering squad provides covering fire like the Land-mine squads but also provides the rear guard during the withdrawal of the of the other elements after the tank-destroying mission was completed.

On Okinawa the Japanese organised an independent antitank company (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). It was considered a suicide unit and was formed from 100 men pulled out of the line-of-communication troops. In this case they were only armed with satchel charges.

“Human bullet” assaults (nikuhaku kōgeki)

“Human bullet” assaults (nikuhaku kōgeki) where when Japanese tank hunter teams rushed enemy tanks in close quarters combat (CQC) (Cox, 1990; Frank, 2021; Huber, 1990). The attackers tried to remain concealed until the enemy escorting infantry was driven off, then they assaulted the tank. The attackers would throw incendiary bottles (kaenbin), explosive satchel charges, reinforced grenades or mines. Or charge with a explosive on the end of a pole. Failing that they would leap on top the machines and insert grenades. “Human bullet” assaults were suicidal in nature, and the men were not expected to survive. The men were advised to attack “with spiritual vigour and steel-piercing passion” (Williamson, 2015).

Most of these anti-tank weapons were not powerful enough to breach the tank’s hull, but they could immobilise it (Huber, 1990). This would allow the Japanese attackers to destroy the thank at their leisure with Molotiv cocktails. American crews tended to abandon stalled tanks, hoping to recover them after dark, so Japanese engineers made a point of destroying immobilised tanks before dark.

The weapons of the Japanese tank-hunters were very short range (9 m) (Williamson, 2015). They would throw hollow-charge grenades or satchel charges on to the tank or thrust the explosives beneath the tank or into a track. Soldiers often strapped the exposives to their bodies and flung themselves beneath the tanks’ tracks.

Individual suicide tank hunters

The Japanese also made use of individual suicide attacks, often from concealed ambush positions (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). This type of attack became more common as the war progressed. The individual would conceal themselves as close as possible to the path of the approaching tank. When the tank is close enough the soldier would dash out and try to destroy or immobilise the tank using one of several explosive devices. Even better is the individual would conceal themselves directly in the path of the Allied tank and explode their device when the tank was overhead. One option was for the soldier to sit in a fox hole with an aerial bomb between their knees; they would try to detonate the bomb when an Allied tank rolled overhead. More commonly the weapons would be mines, hand grenades or Molotov cocktails.

Man portable anti-tank weapons

The Japanese issued a number of weapons to their tank hunters.

Shoulder-Pack Antitank Mine

The Shoulder-Pack Antitank Mine was intended for individual suicide tank hunters (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). The mine was a wooden box, about 28 cm square, weighing 7-9 kg. The rope shoulder straps allowed the solider to carry it on their back. They would wait, concealed, and rush out when an enemy tank approached, throw himself between the tracks, and pulls the detonation cord. The mine would explode 1 to 3 seconds later.

Sack-type Mine

The Sack-type Mine was improvised from canvas bag filled with TNT (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). It was used at close range, either thrown on the tank or underneath. The time fuze was set to go off after 1-2 seconds. About 5 kg would be effective against a light tank and 7-10 kg against a medium or heavy tank.

Type 3 (1943) Conical Hand-Thrown Mine

The Type 3 (1943) Conical Hand-Thrown Mine had a bowl-shaped wooden base, 7 cm in diameter, connected by an explosive-filled truncated cone to a “Universal”-type fuze assembly (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). The soldier used a 25 cm long tail of hemp-palm fibers or grass was attached to the igniter at the upper end of the mine to afford greater accuracy when throwing, and to cause the mine to strike base-first. The Japanese claimed it could penetrate 7 cm of side armour.

Pole Charge

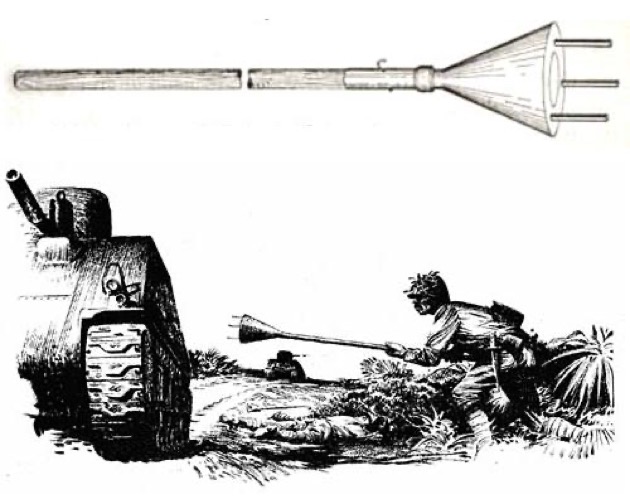

The Pole Charge was usually a Type 93 antitank mine fastened to a long bamboo pole. However, inmprovised containers filled with high explosive were also affixed to poles. The soldier would try to push the charge under the tank tracks.

Type 99 (1939) Magnetic Demolition Charge

The Type 99 (1939) Magnetic Demolition Charge had eight separate sticks of TNT, assembled to form a circle (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). Four magnets are attached to the cover at right angles to each other by a strong canvas ribbon sewn to the cover.

Suction-Cup Mine

Suction-Cup Mine resembled a lunge mine, with an explosive at the end of a pole (Military Intelligence Division, 1945). But the explosive was attached to the target by two suction cups.

Shitotsubakurai lunge mine

The Shitotsubakurai lunge mine first appeared in 1944 in the Phillipines and was officially introduced in 1945 (Military Intelligence Division, 1945; Wikipedia: Shitotsubakurai lunge mine). The weapon a stick, the end of which had metal container enclosing a conical hollow charge anti-tank mine. The three legs attached to the base gave a stand-off of 15 cm. It was mainly used against American armour. Tests showed it could pierce 15 cm of armour but was not terribly effective in the field. There are no reports of it having been successfully applied. Despite this lack of success the lunge mine was used in the First Indochina War.

(Source: United States. War Department. Military Intelligence Service – Intelligence Bulletin Vol.03, N°07, march, 1945, page 64)

Kamikaze “special attacks” (tokkō)

Kamikaze attacks began in September 1944 (Chen, 2006). They were a logical extention of the “Human bullet” assaults but applied to air-naval warfare. In these “special attacks” (tokkō) the pilot carried the bomb all the way to the target enemy ship.

References

Chen, C. P. (2006). Tokko “Kamikaze” Special Attack Doctrine. World War II Database.

Cox, A. D. (1990). Nomonhan: Japan Against Russia, 1939, Volumes 1-2. Stanford University Press.

Frank, R. B. (2021). Tower of Skulls: A History of the Asia-Pacific War, Volume I: July 1937-May 1942. W. W. Norton & Company.

Huber, T. M. (1990). Japan’s Battle of Okinawa, April–June 1945. Leavenworth Papers, 18. United States Army Command and General Staff College.

Military Intelligence Division. (1945). Japanese Tank and Antitank Warfare. Special Series No. 34. War Department. Washington D.C.

Wikipedia: Shitotsubakurai lunge mine

Wikipedia: Type 97 automatic cannon

Williamson, M. (2015). Japanese Suicidal Snipers and Anti-Tank Squads. Forlorn Hope – Suicide Weapon.

Zaloga, S. J. (2018). The Anti-Tank Rifle. Osprey Publishing.

Great information. It would be interesting to also read about the tactics, techniques, and procedures developed by the allies to protect against these types of assaults.